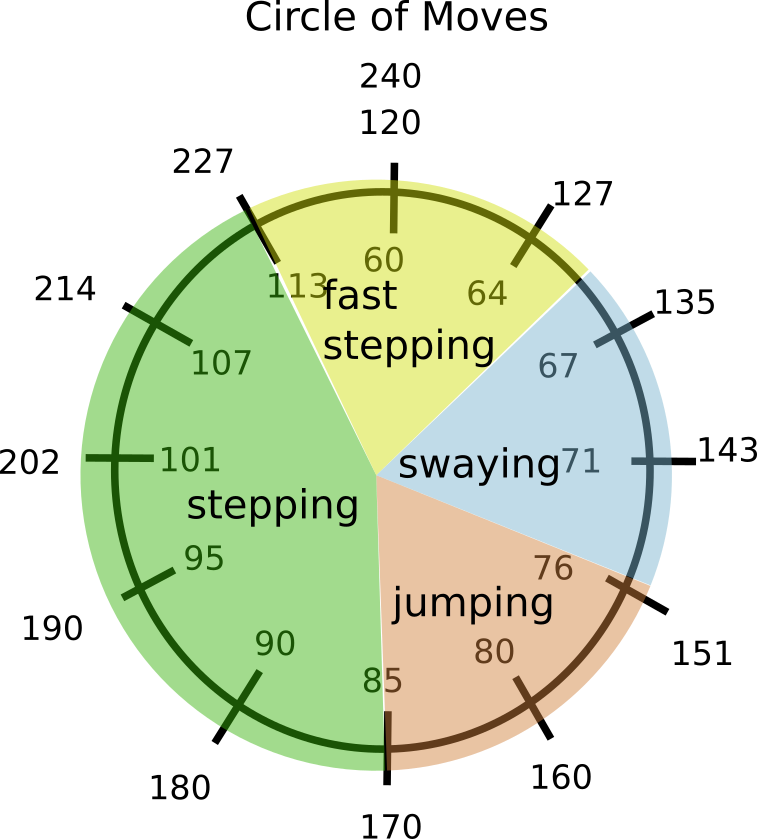

If you jump gently in place like when dancing or at a rally, you’ll notice that there’s a tempo at which jumping is comfortable. Slower than that, you’d need to jump too high and it’s tiring. Faster than that, you . For me it’s about 160 bpm. The tempo will be similar for most people, because it does not depend on body size or weight, but only on how high you’re jumping.

So if you take a person whose natural response to rhythmical music is jumping, and you play them a beat in 113 bpm, they will be confused. They might try jumping and realize that they have to leap up about 20cm into the air and it’s exhausting. Double the tempo (226bpm) will be too fast, it would be more like shaking rather than jumping.

But there are also people who are more used to ballroom dancing, which is based on stepping rather than jumping. Normal walking would be around 60-115 steps per minute. Step-based dances tempos generally range from about 70 bpm till 135 bpm, or 140-270 steps per minute. This covers almost the entire circle. I have some experience dancing forró; tempos around 70 bpm would be for training, and for dancing are around 80-120 bpm.

There are people who like swaying. My natural tempo for swaying would be around 70 bpm. And the most “unswayable” tempo would be on the opposite side of the circle, around 100 bpm. I tried swaying at 100 bpm, I can kind of do it, but it feels forced, unnatural, and tiring.

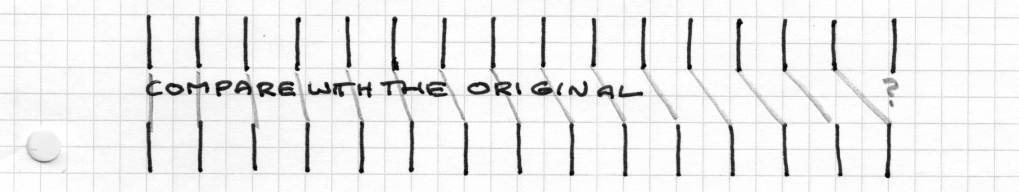

I tried to map the most basic types of moving to the music onto the circle of tempos, and here’s what I came up with.

Please take the above with a pinch of salt, every person is different, and I’m sure there’s someone who jumps at 113 bpm and sways at 95 bpm. But overall, I think these are the general tendencies.

So when you are working on a new piece of music, you can use the above to have an idea what kind of moves will be the most comfortable when listening to your tune.